Who Is Responsible for Turkey’s Syria Predicament?

Last month, a French journalist’s question that set off a tense exchange with the Turkish president in Paris over arms shipment by the Turkish intelligence to the radical groups in Syria touched off a lasting debate at home, in Turkey, about the country’s thrust to the Syrian conflict and how things went wrong over the past seven years.

Mehmet Barlas, an acolyte and surrogate of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, forayed into the debate and claimed, in an embarrassing negation of Mr. Erdogan’s narrative in Paris, that Turkey once helped terrorist organizations in Syria. He then pinned much of the blame for everything went wrong in Syria on former Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu.

The legacy of Mr. Davutoglu, both as a chief advisor, foreign minister and prime minister, is again at the heart of national conversation and political debate. Majority of the punditry and journalists see academic-turned-politician as the major architect of Turkey’s foray into the Syrian war. When Mr. Barlas singled out the former prime minister as someone who pushed the country into the Syrian abyss, Mr. Davutoglu leapt into the defense of Turkey’s Syria policy and emphasized that it was a collective decision taken in the upper echelons of the Turkish state, not taken by one individual — by himself.

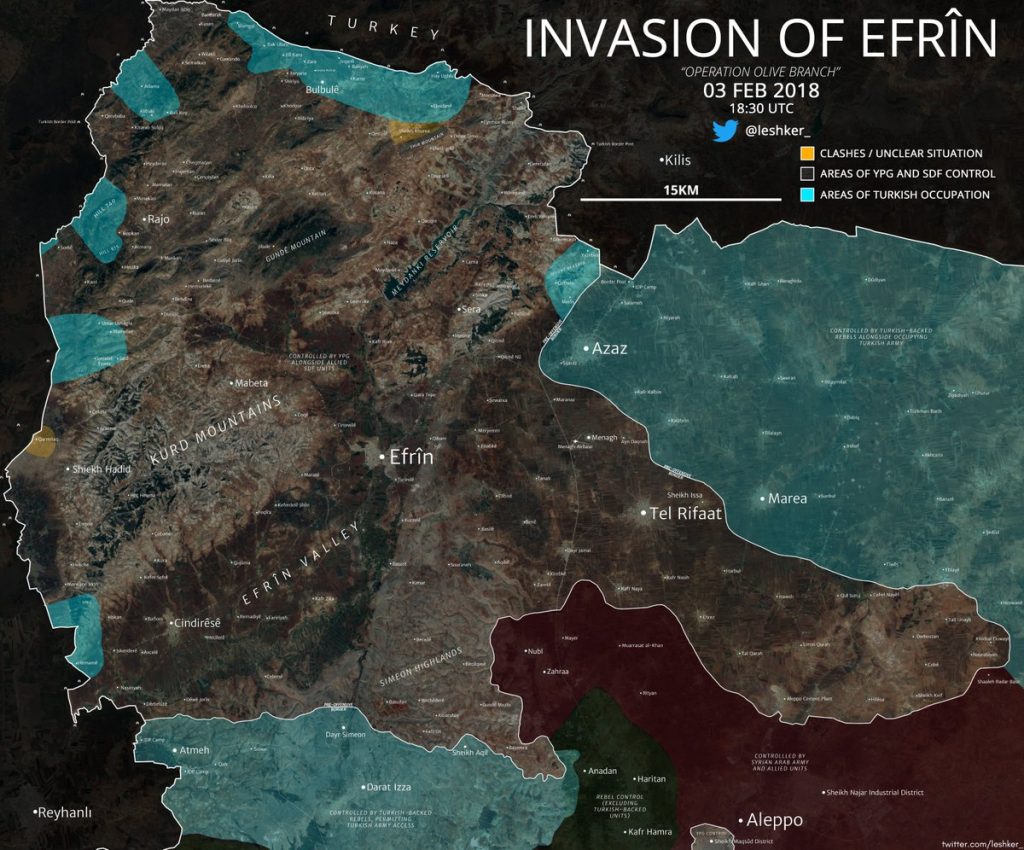

On Jan. 20, Turkey’s involvement in Syria’s protracted and multi-layered conflict has taken a new turn when the Turkish forces launched an offensive to uproot Kurdish militia from the northwestern enclave of Afrin. The “Operation Oil Branch” was a new front in a web of wars within the Syrian civil war and marked a shift in Turkey’s ever-evolving Syria strategies.

Ankara scaled back its lofty goal of regime change in Damascus to keep a check on an expanding militia the Turkish government views as an emerging threat against its national security interests.

The initial signs do not augur well for the arduous task of capturing the Kurdish-held town. The Turkish military announced on Sunday that 31 soldiers have been killed and 143 soldiers wounded during clashes with People’s Protection Units (YPG).

And on Saturday, the former prime minister again entered the political conversation when he expressed no repentance over his choices regarding formulation of Syria policy seven years ago. It has ignited an ensuing debate over his exact role and how things for Turkey went awry in Syria.

But was Mr. Davutoglu the sole responsible figure for the predicament that hamstrung Turkey in Syria’s multifaceted conflict?

“You cannot blame Ahmet Davutoglu for mistakenly predicting that Assad’s downfall was imminent, since this was an assessment shared by many at the beginning of the Syrian Civil War,” Gallia Lindenstrauss, Research Fellow at Tel Aviv-based Institute for National Security Studies (INSS), told Globe Post Turkey.

However, she added, “you can say that Turkey for the first time in the history of the Republic actively tried to push for regime change and this has been one of the reasons why the war in Syria has been lingering on.” She said: “Still, it is not only Turkey’s fault that the Civil War in Syria has also become a regional proxy war, but also other regional powers are to blame.”

When the first protests broke out in March 2011, Turkey had been in a unique position with a potential to steer the course of events on the ground by courting President Bashar al-Assad to enact reforms. But Ankara’s urge for reforms fell on deaf ears in the Syrian capital.

The former foreign minister, as he himself put it, went to Damascus 62 times in the past decade before the uprising, a staggering figure itself spoke to the nature of cordial relationship Turkey’s ruling AKP had cultivated with Syria since it came to the power in 2002.

Treated as a pariah by the international community, Syria’s Assad enjoyed such a strong friendship from a country, which was then an aspiring Muslim democracy, an EU candidate and a NATO member. Ankara gave Assad what he craved for to polish his image and to reduce Syria’s international isolation.

At one point, President Erdogan even went to the famous Turkish holiday resort of Bodrum in the Aegean coast for a family vacation along with the Assad family. The 2008 picture was a testimony to the bond of chemistry built between two leaders.

But with the Arab Spring, which swept political landscapes across the Middle Eastern countries, things quickly fell apart. The regional wave of unrest unleashed the social forces of revolution and upheaval also in Syria, heralding a civil conflict which has lasted to this day.

“Davutoglu was the chief architect of Turkey’s deep involvement in Syria – he pressed an assertive line in the hopes of protecting fellow Muslims from the brutal Assad regime and increasing Turkey’s stature on the world stage,” Max Hoffman, the associate director of National Security and International Policy at American Progress, told Globe Post Turkey, ascribing a greater role to the former foreign minister in guiding Ankara’s policies.

“Sadly, Syria has become a bloody quagmire for all the involved parties, with the Syrian people suffering the worst consequences,” he noted.

The former foreign minister, Mr. Hoffman argued, had the support of Erdogan in taking this assertive stance, in part because it benefited Erdoğan politically to be seen as a big player, in part because Syria is of genuine and crucial interest to Turkey, and in part because Erdogan truly believed in the moral imperative to help the Syrians.

The prime minister was resolute and unrepentant when he offered a reassessment of how the government crafted its policies toward an unfolding social uprising in 2011.

“I have never had regret about Syria,” Mr. Davutoglu said in an evident display of self-righteousness. “As always,” he averred, “our Syria policy over the past seven years has been honest, principled and strategic.”

He shrugged off the public questioning of his ideas that steered Mr. Erdogan’s approach to Syria.

His unapologetic stance, however, did not spare him from criticism from his own party as well. Deputy Prime Minister Numan Kurtulmus was one of the senior Justice and Development Party (AKP) figures who indirectly pointed him as the main figure who plunged Turkey into Syrian morass.

But the reality appears to be more complex; arguments centered on ‘one-actor’ explanatory scheme ring hollow.

“When the Syria policy fell apart in the wake of Turkish missteps, Russia’s intervention, and the world’s refusal to stop the killing in Syria – Erdogan jettisoned Davutoglu as the scapegoat,” Mr. Hoffman said.

But, he explained, the Turkish policy that replaced Davutoglu’s approach is if anything more aggressive.

Turkey has given up on the goal of toppling Assad and is now focused on eliminating Kurdish influence – this has actually led to more Turkish military adventurism and more overreach from Erdogan, not less; he noted, expounding on the transformation of Ankara’s policies.

Kobani a Turning Point For Turkey

What landed the former foreign minister at the center of the political controversy was his ambitious policy formulation called “zero problems with neighbors.”

The author of “Strategic Depth” offered a blueprint of a new foreign policy in existential contrast to realist and cautious Republican tradition, proposing a pro-active diplomacy to make Turkey a central player in the region. In his official capacity, he guided Ankara’s foreign policy for more than a decade.

Both the nature and definition of success regarding the Davutoglu doctrine was measured by this proposition: ‘zero problems with neighbors.’

When Turkey, at some point, plunged into a state of turbulent and problematic relations with almost all neighbors in early 2010s, the formula has become a source of mockery in the eyes of critics, at home and abroad. But such reductionist reading is both inaccurate and unfair given the diverse set of factors that shaped the course of regional politics and Turkey’s policies at play, undermining the complacent scholarly approach to place the entire blame on one single actor.

Still, his theorizing and formulation unwittingly unraveled with the Arab Spring when Turkey interfered in regional politics in a way unseen in republican memory.

For Mustafa Gurbuz, a nonresident policy fellow at Washington-based Arab Center, at the core of Davutoglu’s neo-Ottomanism was Kurds as potential allies, differentiating cooperative Syrian Kurds from PKK commanders.

It is important to remember two critical turning-points that led to the fall of Neo-Ottomanism, he pointed out.

“First, the Kobani impact in 2014: Turkey’s mishandling of the issue in the face of ISIS [Islamic State] threat against Kurdish civilians led YPG not only gaining the sympathy of the world but also securing military support from the United States,” he said.

“Second, the HDP’s electoral victory in 2015, which has brought Erdogan and Turkish nationalist party (MHP) together, and thus, derailment of the peace process.”

The confluence of domestic and regional factors dramatically changed the complexion at the expense of Turkey’s interests. The collapse of the fragile peace process with outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) in 2015, the unexpected rise of Kurdish militia in northern Syria and subsequent alarmism in Ankara altered its priorities.

Russian foray into Syria, Turkey’s downing of a Russian warplane, Iran’s unswerving commitment to the Assad regime, Iranian-backed militia, Hezbollah, the ISIS factor, the U.S. air campaign to combat ISIS all have left a profound impact over the course of events that deadlocked the seven-year war.

But Turkey’s initial backing of armed rebellion seemed to be detrimental to its own interests, setting in motion of a chain of events that eventually veered off its control and reach.

The pace of change on the ground also reversed friends and foes in constant alteration. Russia, which has supported the Syrian president has emerged as a new-found ally for Turkey while its NATO ally, the U.S., is now seen an adversary by Ankara over its alignment with the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF).

Who is responsible for Turkey’s Syria story remains to be a matter of ensuing controversy with no easy answer available. Not now, maybe not in the future as well.

Comments are closed.