The takeover of Afrin from the Syrian Kurdish militia unleashed a sense of euphoria among the Turkish nationalists and President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s loyal supporters. A jubilant mood swept social domain with municipalities taking the lead for celebrations of the military victory.

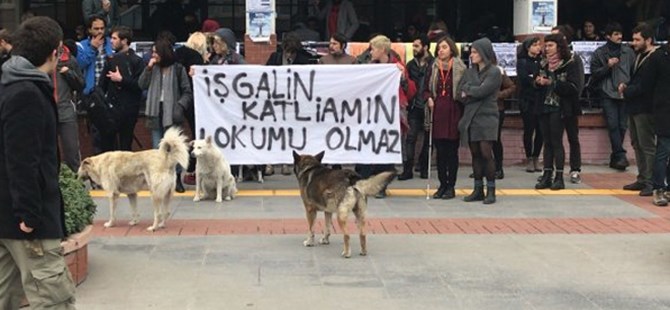

But when a group of students at Bogazici University began to distribute candy and Turkish delight on campus to mark the fall of Afrin, it sparked a protest from other students who depicted Turkey’s military offensive as “invasion.”

It was a risky expression of discontent in a country where most people support the war and hundreds of people were imprisoned for criticizing it. Unsurprisingly, the police came for them as well.

Between March 22 and April 2, 26 students from Istanbul Bogazici University have been detained in total. While 10 of them were released after a brief detention, 16 remained in police custody. Out of them, nine have been imprisoned after the court hearing on Tuesday.

The clash of interpretation over how to define Afrin campaign at a university campus set off a bitter political controversy, with far-reaching implications for Turkey’s universities. The protest aroused a swift reaction from President Erdogan who stepped in and portrayed protesting students as “terrorists.”

He charged them with treason and betrayal of national values. What irked many was his threat to rob left-leaning students of their right to higher education.

“We won’t give these terrorist youth the right to study at these universities,” the president snapped them with indignation, after announcing an investigation into the students.

The trial of left-leaning students has, therefore, become an embodiment of a new brewing political war over Turkey’s university landscape.

Outside the courthouse on Tuesday, families of students and their friends chanted slogans like “Right to education cannot be prevented. Freedom to youth, university and Bogazici.”

“We will continue to defend free thought at universities. Let the detained released and end pressure on universities,” Tilbe Akin, a female student, told media.

A parent of a student said that their children performed the right to freedom of expression. “They used the liberties that must exist in a university environment. We came here to take our children.”

“We endure a process. During this process, either my kid or other’s children were detained,” Mustafa Kok, another parent, said in disbelief. “We never think that our detained children did anything wrong that would require punishment by law.”

The police raids against Bogazici University students marked a new escalation in an expanding crackdown on academia and campuses.

President Erdogan’s portrayal of university students as “terrorists” sent shudders through intelligentsia and academia, reminding the dark days of the Cold War when the Turkish college campuses have been divided along the lines of political affiliation with the right and left.

Communists or left-leaning students and nationalists were the two dominant forces in the 1970s that were vying for control of campuses in a struggle to define where Turkey belongs, to NATO-led Western Europe or the East, what should be the political system and what would be the role of religion in public and political life. Culture wars became political wars and a bitter contest over national identity did not only spur intellectual soul-searching at universities or in public domain but also sparked violence.

Apart from streets and Parliament, universities also emerged as defining elements of the political split and ideological contest.

With violence becoming the expression of thought, the battle of ideas soon turned to battles on campuses throughout the period, and the whole university system appeared to fall apart.

When the military intervened to stop the carnage in 1980, around 5,000 people were killed in the political violence that fractured society, crippled higher education and sew seeds of lasting divisions.

Though the military coup inflicted a severe blow to formidable might of student unions and ceased violence between rival factions at campuses, tension and sporadic fights have never completely been eradicated. But it never reached the levels of the late 1970s as a certain degree of civic dialogue and norms took hold.

Bogazici University, the country’s most liberal face of higher education, has found itself at the center of a sprawling political dispute over university landscape. The ruling AKP’s policies over academia have already touched off debates about the direction and management of Turkey’s fraying education system teemed with political indoctrination, nepotism, brain-drain and evaporation of merit-based approach.

After the botched coup, more than 7,000 academics have been purged without any due process. Even before the 2016 putsch, a legal investigation had been launched against more than 1,000 academics over a peace memorandum that called the cessation of army operations against outlawed Kurdish militants in urban centers to avoid destruction of residential areas and civilian losses. Dozens of academics from Bogazici University also became the target of the ever-evolving probe.

The latest police raids, however, struck a particular chord, whipping up a strong resentment among the country’s most elite university academics and students.

Socialist student groups who are in the crosshairs of the president vowed to fight against any injustice. A group speaking on behalf of the arrested students said arrests and police crackdown aim to terrorize and silence critical students.

“We won’t condone this pressure. We won’t be silent,” the group representatives noted, according to Cumhuriyet daily.

Professor Rifat Okcabol said the operation aims to teach a lesson to Bogazici University, which the government deems non-loyalist.

“The problem is while universities were forced to fit an ideal mode, Bogazici, for the time being, has yet to reach the desired point,” he said, elaborating on the government’s policies to design universities to toe its line.

“Almost at every university, there is a reactionary discourse, support for the war, endorsement of the presidential system, and blessing for every government initiative, there is no such a thing from Bogazici, at least for now.”

President Erdogan’s push for the executive presidency and his adoption of Islamist discourse has also had reverberations throughout campuses, exposing emergence of new fault lines among students.

College students and academics who came against 2017 referendum, which enabled a transition to an executive presidential system, later became targets of the political clampdown.

The latest Afrin offensive also became the mirror of social cleavages and divisions across colleges. And Bogazici University was at the center of political conversation over a brief squabble among students about Turkey’s military endeavor in Afrin. Some students appeared to be heartfelt supporters of Erdogan’s military campaign, some not.

Comments are closed.